By Hoovering Up the Web, AI Is Poisoning Itself

What does it mean for LLMs when the web has been strip-mined clean, content providers have locked their doors, and there’s barely a trickle of new data to scrape?

There's been a lot of pixels spilled recently about the perils of AI companies hoovering up all the data on the internet, whether they have "permission" to or not. We'll go into "permission" a bit later - there's a reason we wrapped the word in scare quotes. But what does it mean for LLMs when the open web has been strip-mined clean, content providers have locked their doors, and there’s barely a trickle of new data to scrape?

The Dangers of AI Scraping

AI companies are treating the internet like an all-you-can-eat data buffet, and they're not bothering with table manners. Just look at Runway harvesting YouTube videos for training their model (against YouTube's terms of service), Anthropic hitting iFixit a million times a day and the New York Times suing OpenAI and Microsoft over use of copyrighted works.

Trying to block scrapers in your robots.txt or terms of service doesn’t really help in any way. The scrapers who don’t care will scrape anyway, while the more considerate ones will be blocked. There’s no incentive for any scraper to play nice. We can see this in action in the recent paper from the Data Provenance Initiative:

This isn’t just an abstract problem - iFixit loses money and gets its DevOps resources tied up. ReadTheDocs racked up over $5,000 in bandwidth charges in just one month, with almost 10 TB in a single day, due to abusive crawlers. If you run a website and you get hit by a crawler that doesn’t follow the rules? That could be lights out.

So, what’s a website to do? If AI companies aren’t going to play by the rules, expect paywalls to go up, and freely-available content to go down. The free web is no more. All that’s left is pay-to-play.

Is Scraping Even Legal?

Is scraping problematic? Yes. It it legal? Also yes. Web scraping is legal in the US, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and Canada. No country appears to have laws specifically addressing this practice, but courts around the world generally agree that it’s legal to use automation to visit websites that are open for anyone to see, and to make private copies of their content.

People sometimes believe that by placing some printed notice on a web page or in a robots.txt file, they can forbid scraping or other legal uses of their website and its contents. This doesn’t really work. Notices like that have no legal meaning, and robots.txt is an IETF convention that has no force of law. Without some act of confirmation, at a minimum clicking the button marked “I accept the Terms of Service”, you cannot impose conditions on visitors to your website, and even then they are often legally unenforceable.

However, while scraping is legal, there are some limitations:

- Practices that might reduce the usability of a website for others, like hitting it too often or too fast with your web-scraper, may have civil or even criminal consequences in extreme cases.

- Many countries have laws that criminalize accessing computers in unauthorized ways. If there are parts of a website that are clearly not meant to be accessed by the general public, it may be illegal to scrape them.

- Many countries have laws that make it illegal to circumvent anti-copying technologies. If a website has put in place measures to prevent you from downloading some content, you may be breaking the law if you scrape it anyway.

- Websites that have explicit terms of service, and require you to confirm your acceptance of them, can forbid scraping and take you to court if you do it, but the results are spotty.

In the US, there is no explicit law regarding scraping, but efforts to use the 1986 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act to forbid it have failed, most recently in the Ninth Circuit case hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn in 2019. US law is complex, with a lot of court-made distinctions and a system of state and federal circuit jurisdictions that mean that unless the Supreme Court rules on something, it’s not necessarily final. (And sometimes isn’t final even then.)

The EU doesn’t have any specific laws addressing scraping either, but it has been a common and unchallenged practice for a very long time. The Text and Data Mining clause in the 2019 EU Copyright Directive strongly implies that scraping is generally legal.

The biggest legal problems are not with the act of scraping but with what happens after you scrape. Copyright still applies to the data you scrape from the web. You can keep a personal copy, but you can’t redistribute or resell it, not without some potential for legal problems.

Doing large-scale web scraping almost always means making copies of “personal data”, as defined in various data protection and privacy laws. The European GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) defines “personal data” as:

[A]ny information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person;

[GDPR, Art. 4.1]

If you possess a store of personal data regarding any person residing in the EU or activity taking place in the EU, you have legal responsibilities under the GDPR. Its scope is so broad that you should assume it’s true for any large data collection. It doesn’t matter if you collected the data or someone else did, if you have it now, you are responsible for it. If you don’t fulfil your GDPR obligations, the EU can punish you regardless of what country you live in or where the data is stored or processed.

Canada’s PIPEDA (Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act) is similar to the GDPR. Japan’s APPI (Act on the Protection of Personal Information) covers much of the same ground. The UK incorporated most elements of the GDPR into their domestic laws on leaving the EU, and unless amended later, they are still in force.

The US doesn’t have a comparable data protection law at the federal level, but the CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act) has similar terms to the GDPR and applies if you have data about people or activities in the state of California.

Most developed countries have data protection laws that limit, at least in some respects, what you can do with massive data collections from the web. Most of the legal proceedings around the world touching on scraping have been about how the data was used, not how it was collected.

So, web scraping is almost always legal. It’s what happens next that gets complicated.

Is Training AI from Scraping Legal?

Probably.

A web scrape will, in almost all realistic cases, include copyrighted content. The real question is: Can you use copyrighted content to train an AI without permission from the owner?

There are a lot of individual legal points that aren’t fully resolved, but:

- In Europe, Article 4 of the EU Copyright Directive of 2019 appears to make it legal with some caveats.

- In Japan, Article 30(4) of the Copyright Law, as amended in 2018, has been interpreted as allowing copyrighted works to be used to train AI without permission.

- In the US, no law specifically addresses this situation, however, it has been taken for granted for many years that statistical analysis of copyrighted materials is legal, even when the result is a commercial product. Although the lawsuits Authors Guild, Inc. v. Google, Inc. and Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust don’t specifically address AI, they expand the scope of “fair use” under US law so broadly that it is hard to see how AI training could be illegal. The American legal system does not offer an explicit answer and several cases testing this conclusion are making their way through the courts.

A number of smaller jurisdictions have also determined that it’s legal, and to the best of my knowledge, none have found it to be illegal to date.

European copyright law lets owners of copyrighted data restrict the use of their works for AI training by indicating this “in an appropriate manner”. There is currently no guidance on how they should do this.

Japanese copyright law limits the use of copyrighted materials where it might “unreasonably prejudice the interests of the copyright owner”. This typically indicates that a copyright holder would have to show how a specific AI model reduces the economic value of their work to be able to make a case.

We should note that Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, Adobe, and Shutterstock have offered to indemnify any user of their generative AI products who faces a legal challenge on copyright grounds. This is a strong indication that their lawyers think what they are doing is legal under US law.

What Voracious Scraping Means For AI

The AI scraping bonanza is turning the web into a digital Wild West. These scrapers are treating robots.txt like it's yesterday's news, hammering websites like iFixit with endless requests. It's not just annoying - it's potentially web-breaking stuff that's forcing us to rethink how the open internet works. Or how it might not work in the near future. Just from an economic and social point of view, there are so many things that could change:

Trust breakdown: This AI feeding frenzy could lead to a massive trust breakdown across the web. Imagine a future where every website greets you with a skeptical eye, forcing you to prove you're human before you can even peek at their content. We're talking more CAPTCHAs, more login walls, more "click all the traffic lights" tests. It's like trying to get into a speakeasy, but instead of a secret password, you need to convince the doorman you're not a very clever machine.

Limited human-generated content: Content creators, already wary of their work being swiped, are starting to batten down the hatches. We could see a surge in paywalls, subscriber-only sections, and content locks. The days of freely browsing and learning might become a nostalgic memory, like dial-up modem sounds or AIM away messages. If ordinary humans can’t access it, that makes it all the harder for a rogue scraper to get in.

Legal cases: It may be years or even decades before all the legal issues surrounding AI are worked out. We’ve had the Internet for about thirty years, and some of its legal issues are still up in the air today. Whether you’re in the right or not, if you can’t afford to spend years in court finding out what is and isn’t allowed, you have something to worry about.

Small fries go broke, fat cats get fatter: This scraping frenzy isn't just a nuisance - it's putting real strain on web infrastructure. Sites dealing with AI-induced traffic jams might need to upgrade to beefier servers, which isn't cheap. Smaller sites and cool passion projects could get priced out of the game, leaving us with a web (and LLM training data) dominated by those big enough to weather the storm or sign licensing deals with the AI companies. It's a "survival of the richest" scenario that could make the internet (and LLM knowledge) a lot less diverse and interesting. By closing the door on freely-available data, they can then charge an entry fee to the AI corporations, or just license to the highest bidder. Don’t have the money? The bouncer will show you the door.

AI-Generated Data To The Rescue?

The data grab isn't just shaking up websites - it's setting the stage for a potential AI knowledge drought. As the open web pulls up its drawbridges, AI models will find themselves starving for fresh, high-quality data.

This data scarcity could lead to a nasty case of AI tunnel vision. Without a steady stream of new information, AI models risk becoming echo chambers of outdated knowledge. Imagine asking an AI about current events and getting answers that sound like they're from last year - or worse, from a parallel universe where facts took a vacation.

If human-generated data is locked away, companies still have to get their training data from somewhere. One example of this is synthetic data: Data created by LLMs to train other LLMs. This includes widely used techniques like model distillation and generating training data to compensate for bias.

Using synthetic data means not having to jump through hoops to license human-generated data, which as we’ve seen is getting increasingly difficult. It also helps balance things out - a lot of data on the internet doesn’t represent the diversity of the real world. Generating synthetic data can help make a model more representative of reality (or sometimes not). Finally, for the health and legal use cases, synthetic data eliminates the need to sanitize data to remove personally-identifiable information.

However, the flip side of the coin is that future models will also be trained on AI-generated data you really don’t want to be training them on, namely “Slop”: low-quality AI-generated data, like a once-loved tech blog now publishing low-value AI-generated articles under the names of its old staff, AI-generated recipes for unlikely dishes like crockpot mojitos and bratwurst ice cream, or Shrimp Jesus taking over Facebook.

Since this is much cheaper and easier to create than good old-fashioned hand-crafted content, it’s rapidly flooding the internet.

Based on what we’re seeing today, AI-generated content is overtaking available human-generated content. GPT-5 will be trained (in part) on data created by GPT-4. GPT-6, in turn, will be trained on data created by GPT-5. And so on, and so on.

Model Collapse, and How to Avoid It

Using your own outputs as inputs is bad for both humans and LLMs. Even if you’re very selective about how much synthetic data you use and what kind, you can’t guarantee that your model won’t get worse

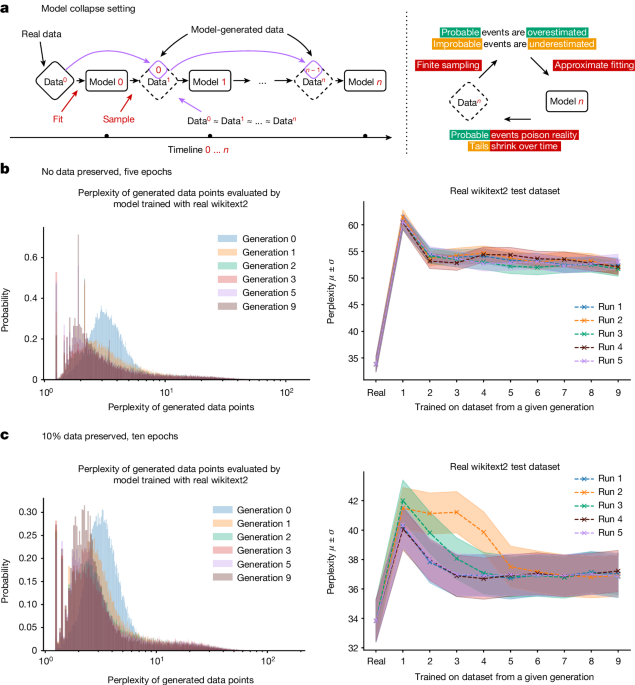

For generative AI models as a whole, the drop-off in quality and diversity of output is experimentally measurable and happens pretty fast. Image-generating models develop anomalies after a few generations, and in one paper, a large language model trained on Wikipedia data that gave coherent and accurate responses to prompts was, by the ninth generation of training on its own output, responding to prompts by repeating the words “tailed jackrabbits” over and over.

This is easy enough to explain: An AI model is an approximation of its training data. An AI model trained on AI model output is an approximation of an approximation. At each training cycle, the difference between the approximation and the “true” real-world data gets bigger and bigger.

We call this “model collapse”.

As AI-generated data becomes more and more widespread, training new models from data scraped from the Internet risks lowering model performance. We have some reason to think that as long as the amount of real, human-made data doesn’t decline, our models won’t get much worse, but they won’t get better either. However, they will take longer to train if we can’t separate the AI-made data from human-made data. New models will get costlier to make, without improving.

The irony is thick here. AI's voracious appetite for data might lead to a data famine. Model Autophagy Disorder is like Mad Cow Disease for AI: Just like feeding beef waste to cows led to a new kind of parasitic brain disease, training AI from growing amounts of AI output leads to devastating mental pathologies.

The good news is that AI can’t afford to replace humanity because it needs our data. The bad news is that it may stunt its own growth by ruining its data sources.

To avoid this foreseeable AI knowledge famine, we need to rethink how we train and use AI models. We’re already seeing solutions like Retrieval-Augmented Generation, which tries to avoid using AI models as a source of factual information and sees them instead as devices for evaluating and reorganizing external information sources. Another path forward is via specialization, where we adapt models to perform specific classes of tasks, using curated training data focused on narrow domains. We could replace purported general-purpose models like ChatGPT with specialist AIs: LawLLM, MedLLM, MyLittlePonyLLM, and so on.

There are other possibilities, and it’s hard to say what new techniques researchers will discover. Maybe there's a better way to generate synthetic data or ways to get better models out of less data. But there is no guarantee that more research will solve the problem.

In the end, this challenge might force the AI community to get creative. After all, necessity is the mother of invention, and a data-starved AI landscape could spark some truly innovative solutions. Who knows? The next big breakthrough in AI might come not from more data, but from figuring out how to do more with less.

What Happens If Only Megacorps Can Afford to Scrape?

For many people today, the internet is Facebook, Instagram, and X, viewed through a black glass rectangle they hold in their hand. It’s homogenized, “safe”, and controlled by gatekeepers who decide (via policies and their algorithms) what (and who) you see and what you don’t.

It wasn’t always like this. Just a couple of decades ago we had user-generated blogs, independent websites, and much more. In the eighties, there were dozens of operating systems and hardware standards competing. But by the 2010s, Apple and Microsoft had won the day, beginning the trend of homogenization.

We see the same thing with web browsers, smartphones, and social media sites. We start off with a burst of diversity and new ideas before the big players hog the ball and make it difficult for anyone else to ply.

That said, while those players did have a monopoly, some smaller fry snuck in anyway. (Take Linux and Firefox, for example). “Underdog makes good” is unlikely to happen with LLMs though. When small players lack the financial clout to get access to varied and up-to-date training data, they can’t create high-quality models. And without that, how can they stay in business?

The giants have got the resources to keep their AI models gorging on a steady diet of fresh information, even as the wider web tightens its belt. Meanwhile, smaller players and startups are left scraping the bottom of the data barrel, struggling to nourish their algorithms with stale crumbs. It's a knowledge gap that could snowball. As the data-rich get richer in insights and capabilities, the data-poor risk falling further behind, their AIs growing more outdated and less competitive by the day. This isn't just about who has the shiniest AI toys - it's about who gets to shape the future of technology, commerce, and even how we access information. We're looking at a future where a handful of tech behemoths might hold the keys to the most advanced AI kingdoms, while everyone else is left peering in from the digital dark ages.

With all the juicy content floating around to be licensed, it’s unlikely one Megacorp will be the one to license it all, like Netflix in the old days. Remember that? You’d sign up for one service and get every show you ever dreamed of. Today, shows are spread across Hulu, Netflix, Disney+, and whatever they’re calling HBO Max this week. Sometimes a show you love can just evaporate into the ether. This could be the future of LLMs: Google has priority access to Reddit, while OpenAI gets access to the Financial Times. iFixit? That data is just no more, merely stored as some dusty embeddings, and never updated. Instead of one model to rule them all, we could be looking at fragmentation and shifting capabilities as licensing rights get juggled between AI vendors.

In Conclusion

Scraping is here to stay, whether we like it or not. Already, content providers are erecting barriers to limit access, while opening the doors only to those who can afford to license the content. This severely limits the resources any one LLM can learn from, while at the same time, smaller companies are being priced out of the bidding war for lucrative content, and the rest of the spoils are being divvied up between the tech behemoths’ LLMs. It’s the post-Netflix streaming world all over again, just this time for knowledge.

While available human-generated data dwindles, AI-generated “slop” is booming. Training models on this can lead to a slowdown in improvement or even model collapse. The only way to fix it is by thinking outside the box - something startups, with their culture of innovation and disruption are ideally suited for. Yet, the very data that is being licensed only to the big players is the very lifeblood such startups need to survive.

By limiting fair access to data, the mega-corporations aren't just stifling competition - they're choking the future of AI itself, strangling the very innovation that could propel us beyond this potential digital dark age.

The AI revolution is not the future, AI is now. In the words of William Gibson: “[T]he future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” It can easily become even more unevenly distributed.