The What and Why of Text-Image Modality Gap in CLIP Models

You can't just use a CLIP model to retrieve text and images and sort the results by score. Why? Because of the modality gap. What is it, and where does it come from?

Semantic embeddings are the core of modern AI models, even chatbots and AI art models. They’re sometimes hidden from users, but they’re still there, lurking just under the surface.

The theory of embeddings has only two parts:

- Things — things outside of an AI model, like texts and images — are represented by vectors created by AI models from data about those things.

- Relationships between things outside of an AI model are represented by spatial relations between those vectors. We train AI models specifically to create vectors that work that way.

When we make an image-text multimodal model, we train the model so that embeddings of pictures and embeddings of texts describing or related to those pictures are relatively close together. The semantic similarities between the things those two vectors represent — an image and a text — are reflected in the spatial relationship between the two vectors.

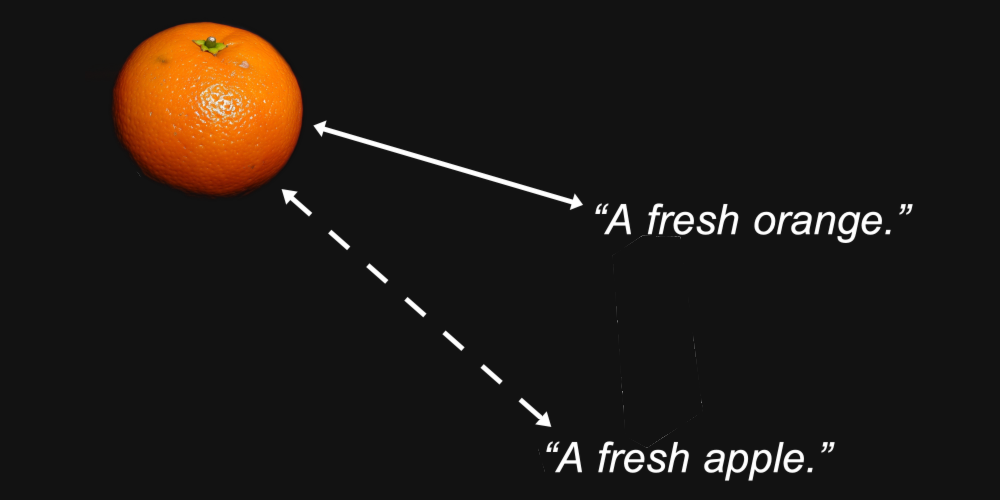

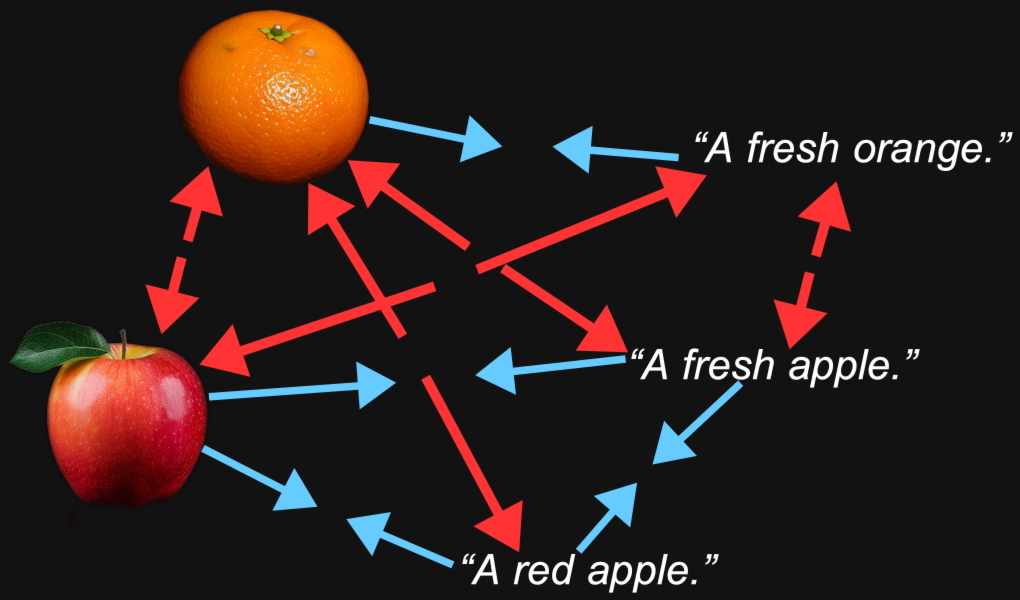

For example, we might reasonably expect the embedding vectors for an image of an orange and the text “a fresh orange” to be closer together than the same image and the text “a fresh apple.”

That’s the purpose of an embedding model: To generate representations where the characteristics we care about — like what kind of fruit is depicted in an image or named in a text — are preserved in the distance between them.

But multimodality introduces something else. We might find that a picture of an orange is closer to a picture of an apple than it is to the text “a fresh orange”, and that the text “a fresh apple” is closer to another text than to an image of an apple.

It turns out this is exactly what happens with multimodal models, including Jina AI’s own Jina CLIP model (jina-clip-v1).

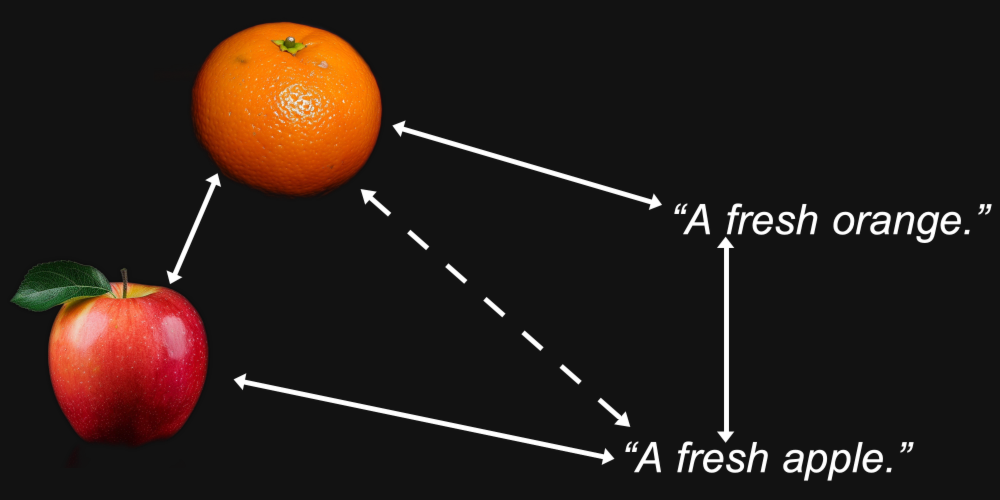

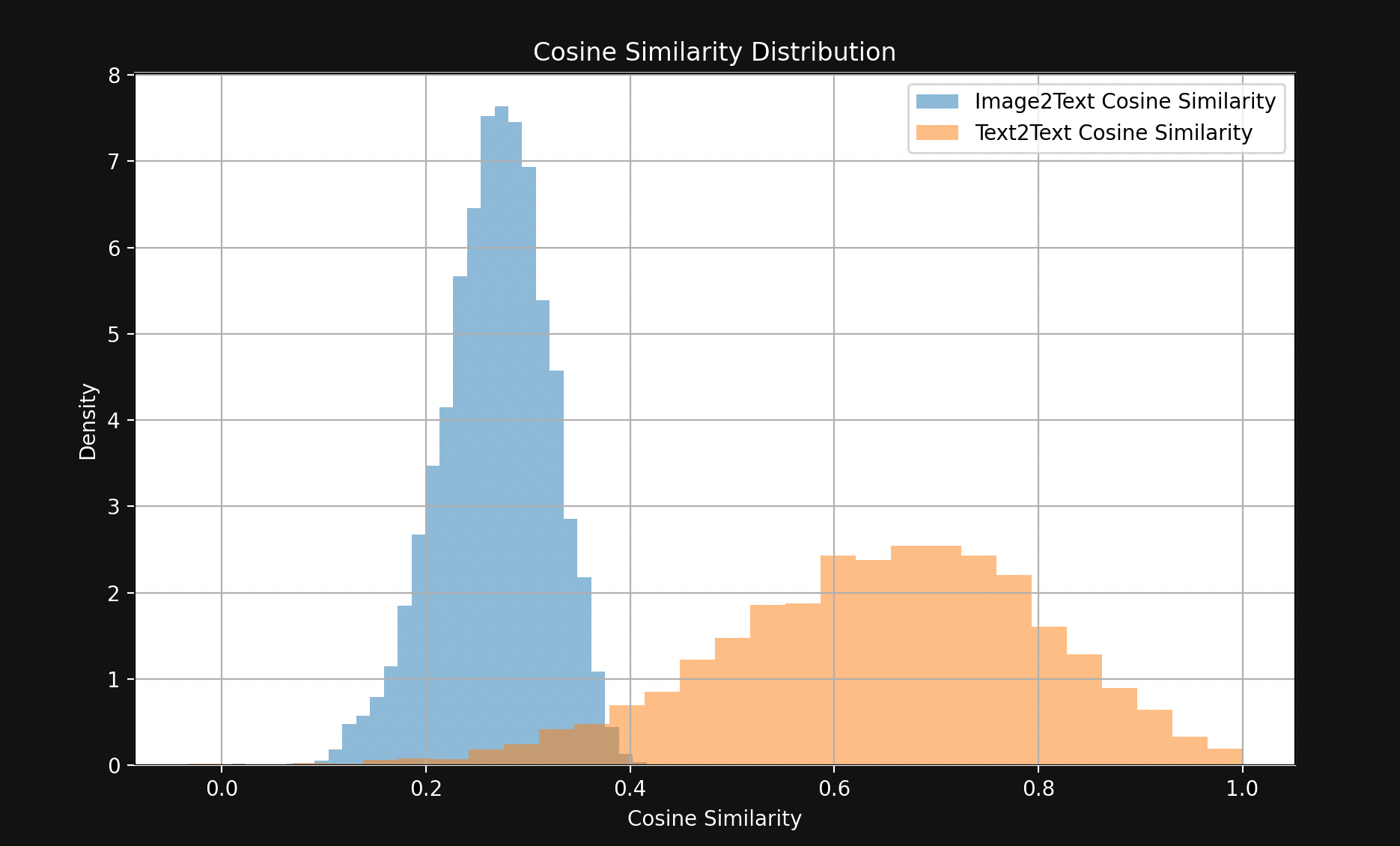

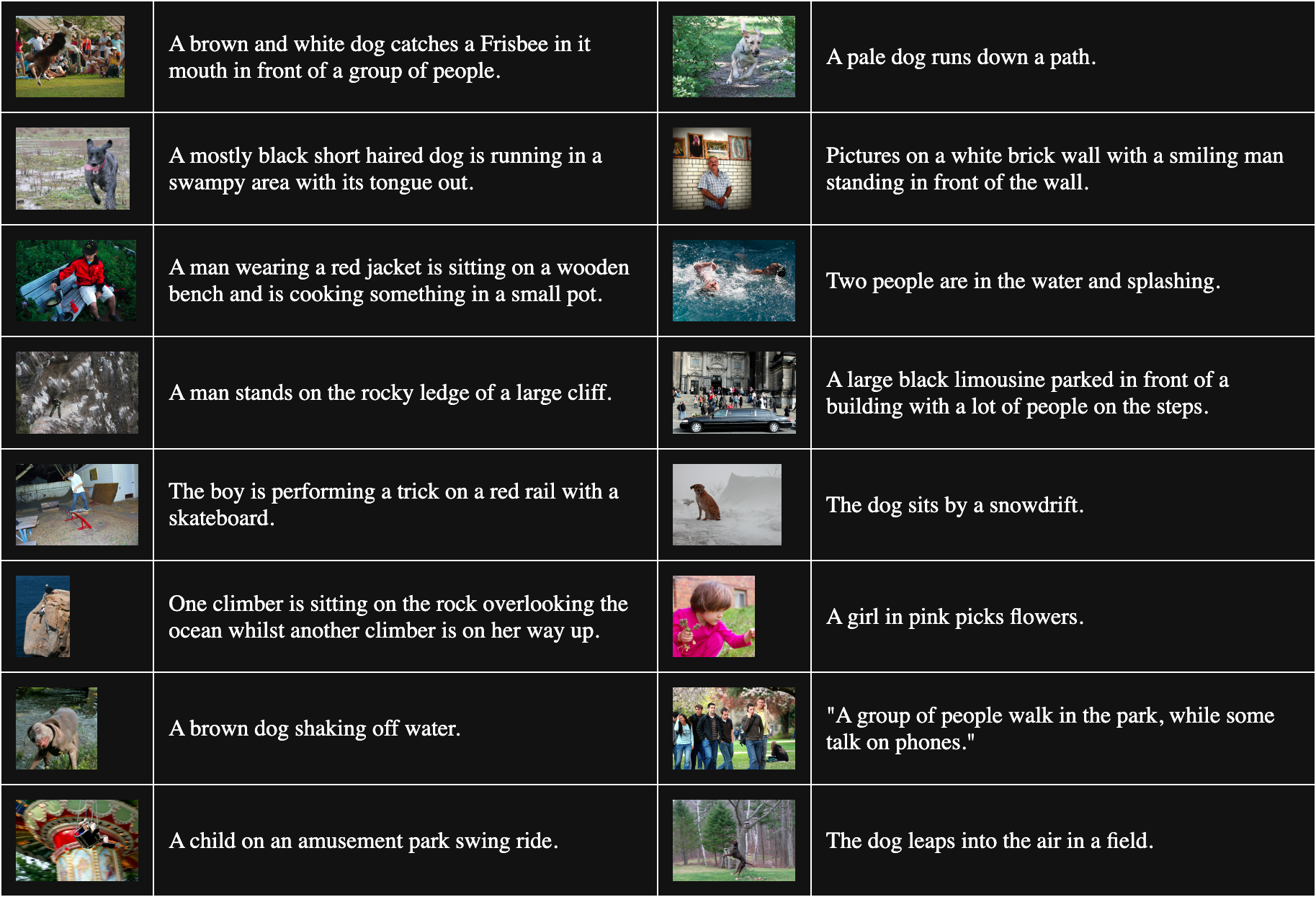

To test this, we sampled 1,000 text-image pairs from the Flickr8k test set. Each pair contains five caption texts (so technically not a pair), and a single image, with all five texts describing the same image.

For example, the following image (1245022983_fb329886dd.jpg in the Flickr8k dataset):

Its five captions:

A child in all pink is posing nearby a stroller with buildings in the distance.

A little girl in pink dances with her hands on her hips.

A small girl wearing pink dances on the sidewalk.

The girl in a bright pink skirt dances near a stroller.

The little girl in pink has her hands on her hips.

We used Jina CLIP to embed the images and texts and then:

- Compare the cosine similarities of the image embeddings to the embeddings of their caption texts.

- Take the embeddings of all five caption texts that describe the same image and compare their cosine similarities to each other.

The result is a surprisingly large gap, visible in Figure 1:

With few exceptions, matching text pairs are much closer together than matching image-text pairs. This strongly indicates that Jina CLIP is encoding texts in one part of the embedding space and images in a largely disjoint part relatively far from it. This space between the texts and the pictures is the multimodal gap.

Multimodal embedding models are encoding more than the semantic information we care about: They’re encoding the medium of their input. According to Jina CLIP, a picture is not, as the saying goes, worth a thousand words. It has content that no amount of words can ever truly equal. It encodes the medium of input into the semantics of its embeddings without anyone ever training it to.

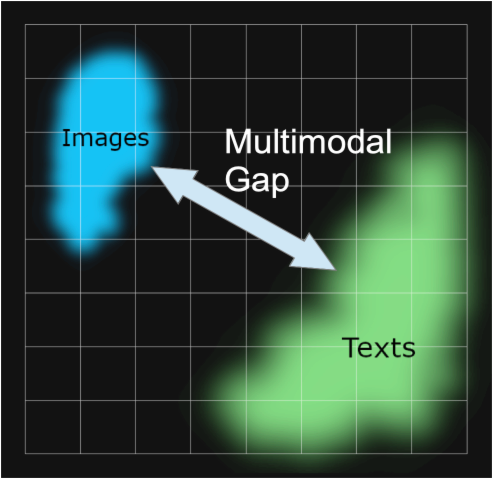

This phenomenon has been investigated in the paper Mind the Gap: Understanding the Modality Gap in Multi-modal Contrastive Representation Learning [Liang et al., 2022] which refers to it as the “modality gap.” The modality gap is the spatial separation, in the embedding space, between inputs in one medium and inputs in another. Although models are not intentionally trained to have such a gap, they are pervasive in multimodal models.

Our investigations into the modality gap in Jina CLIP draw strongly on Liang et al. [2022].

Where Does the Modality Gap Come From?

Liang et al. [2022] identify three major sources behind the modality gap:

- An initialization bias that they call the “cone effect.”

- Reductions in temperature (randomness) during training that make it very hard to “unlearn” this bias.

- Contrastive learning procedures, which are widely used in multimodal models, that unintentionally reinforce the gap.

We’ll look at each in turn.

Cone Effect

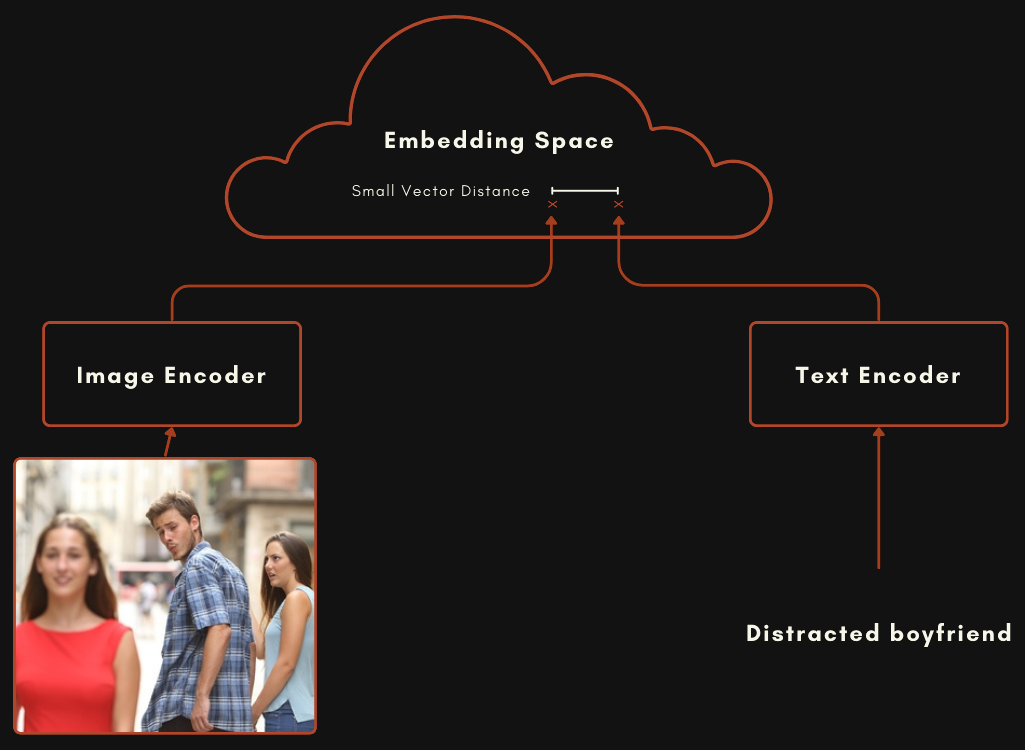

A model built with a CLIP or CLIP-style architecture is actually two separate embedding models hooked together. For image-text multimodal models, this means one model for encoding texts, and a completely separate one for encoding images, as in the schema below.

These two models are trained so that an image embedding and a text embedding are relatively close together when the text does a good job of describing the image.

You can train a model like this by randomizing the weights in both models, then presenting image and text pairs to it together, training it from scratch to minimize the distance between the two outputs. The original OpenAI CLIP model was trained this way. However, this requires a lot of image-text pairs and a lot of computationally expensive training. For the first CLIP model, OpenAI scraped 400 million image-text pairs from captioned materials on the Internet.

More recent CLIP-style models use pre-trained components. This means training each component separately as a good single-mode embedding model, one for texts and one for images. These two models are then further trained together using image-text pairs, a process called contrastive tuning. Aligned image-text pairs are used to slowly “nudge” the weights into making matching text and image embeddings closer together, and non-matching ones farther apart.

This approach generally requires less image-text pair data, which is difficult and costly to obtain, and large amounts of plain texts and images without captions, which are much easier to obtain. Jina CLIP (jina-clip-v1) was trained using this latter method. We pre-trained a JinaBERT v2 model for text encoding using general text data and used a pre-trained EVA-02 image encoder, then further trained them using a variety of contrastive training techniques, as outlined in Koukounas et al. [2024]

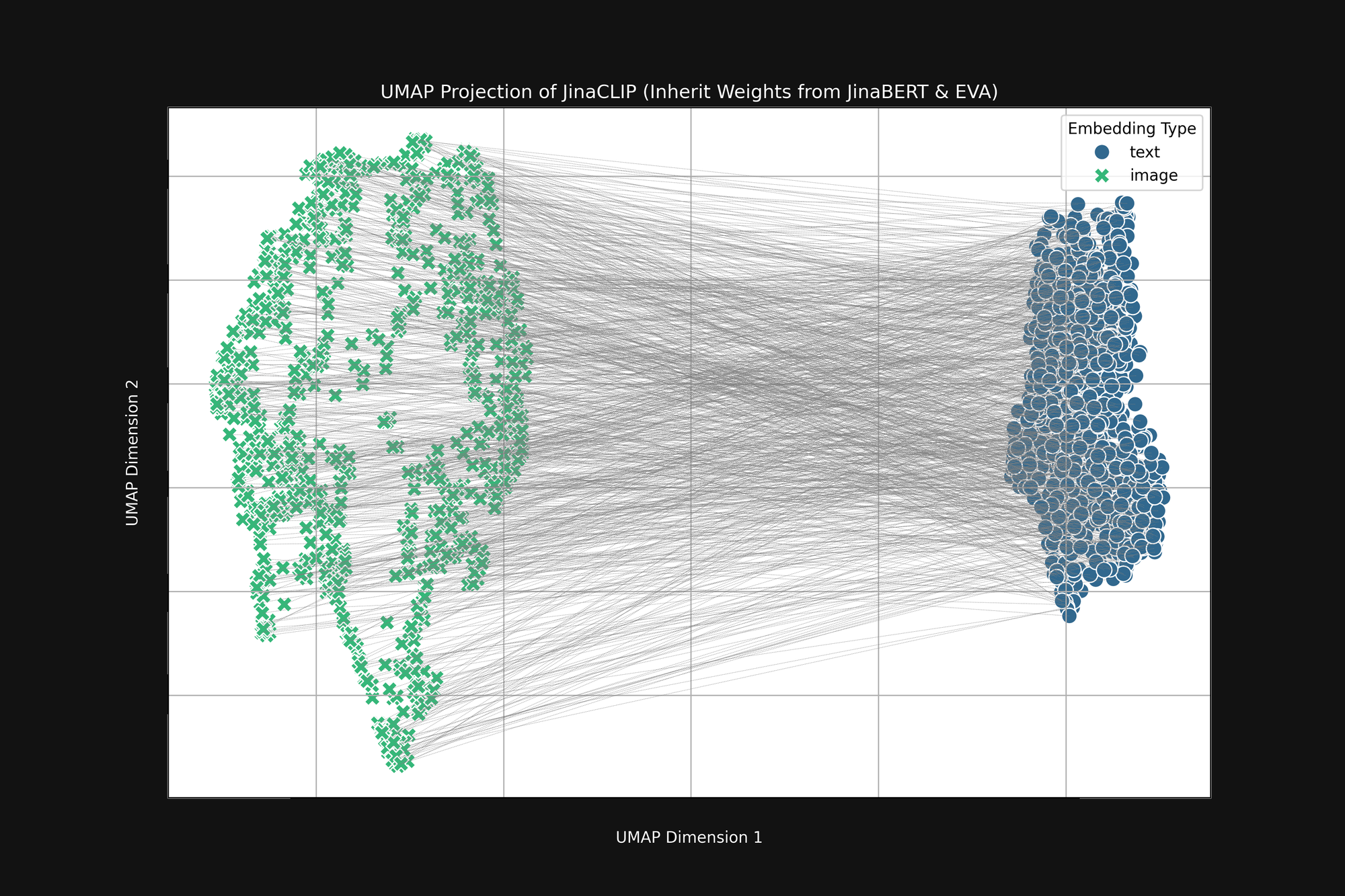

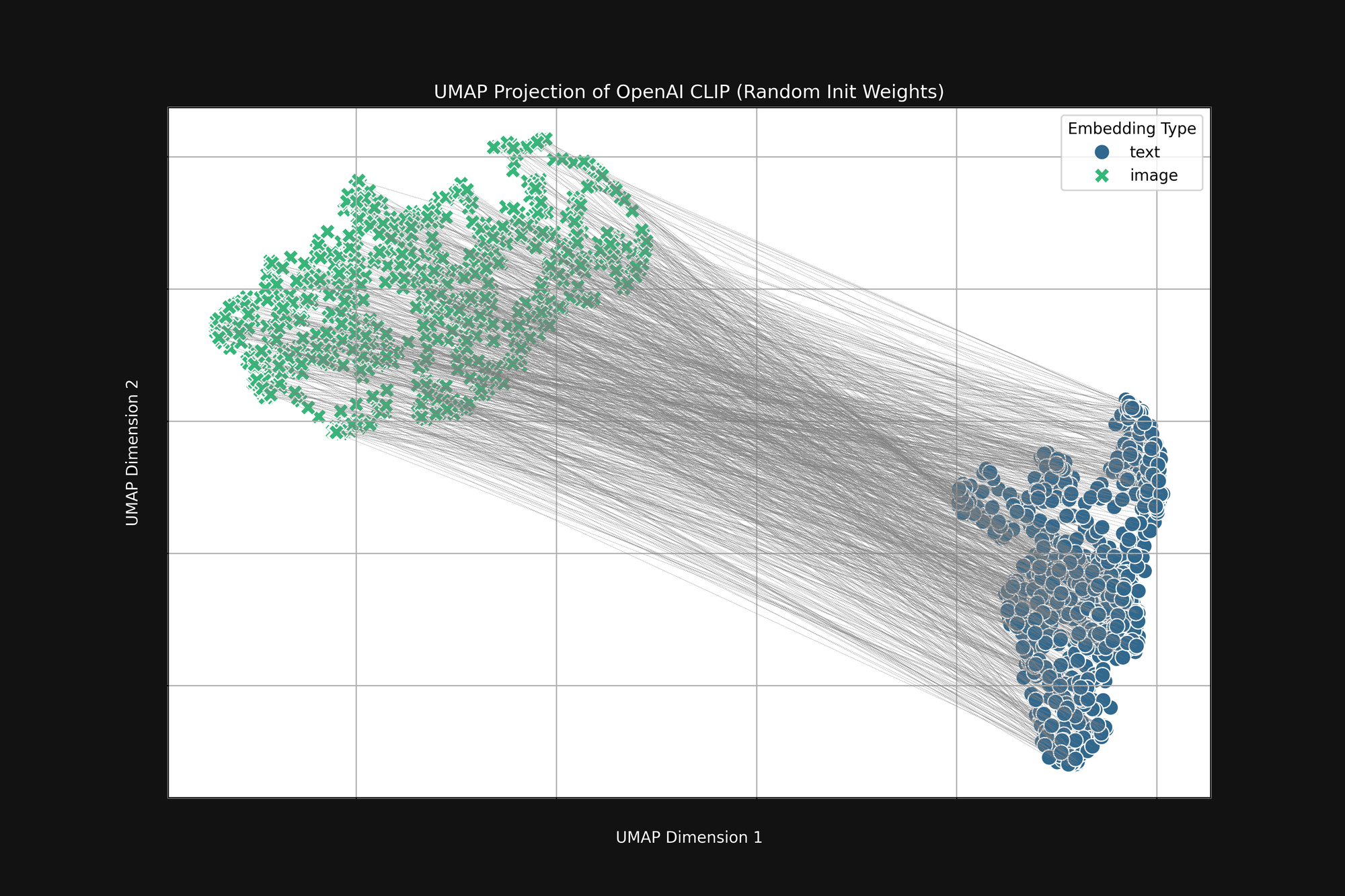

If we take these two pre-trained models and look at their output, before training them with image-text pairs, we notice something important. Figure 2 (above) is a UMAP projection into two dimensions of the image embeddings produced by the pre-trained EVA-02 encoder and the text embeddings produced by the pre-trained JinaBERT v2, with the grey lines indicating matched image-text pairs. This is before any cross-modal training.

The result is a sort of truncated “cone”, with image embeddings at one end and text embeddings at the other. This cone-shape is poorly translated to two-dimensional projections but you can broadly see it in the image above. All the texts cluster together in one part of the embedding space, and all the images in another part. If, after training, texts are still more similar to other texts than to matching images, this initial state is a big reason why. The objective of best matching images to texts, texts to texts, and images to images, is completely compatible with this cone shape.

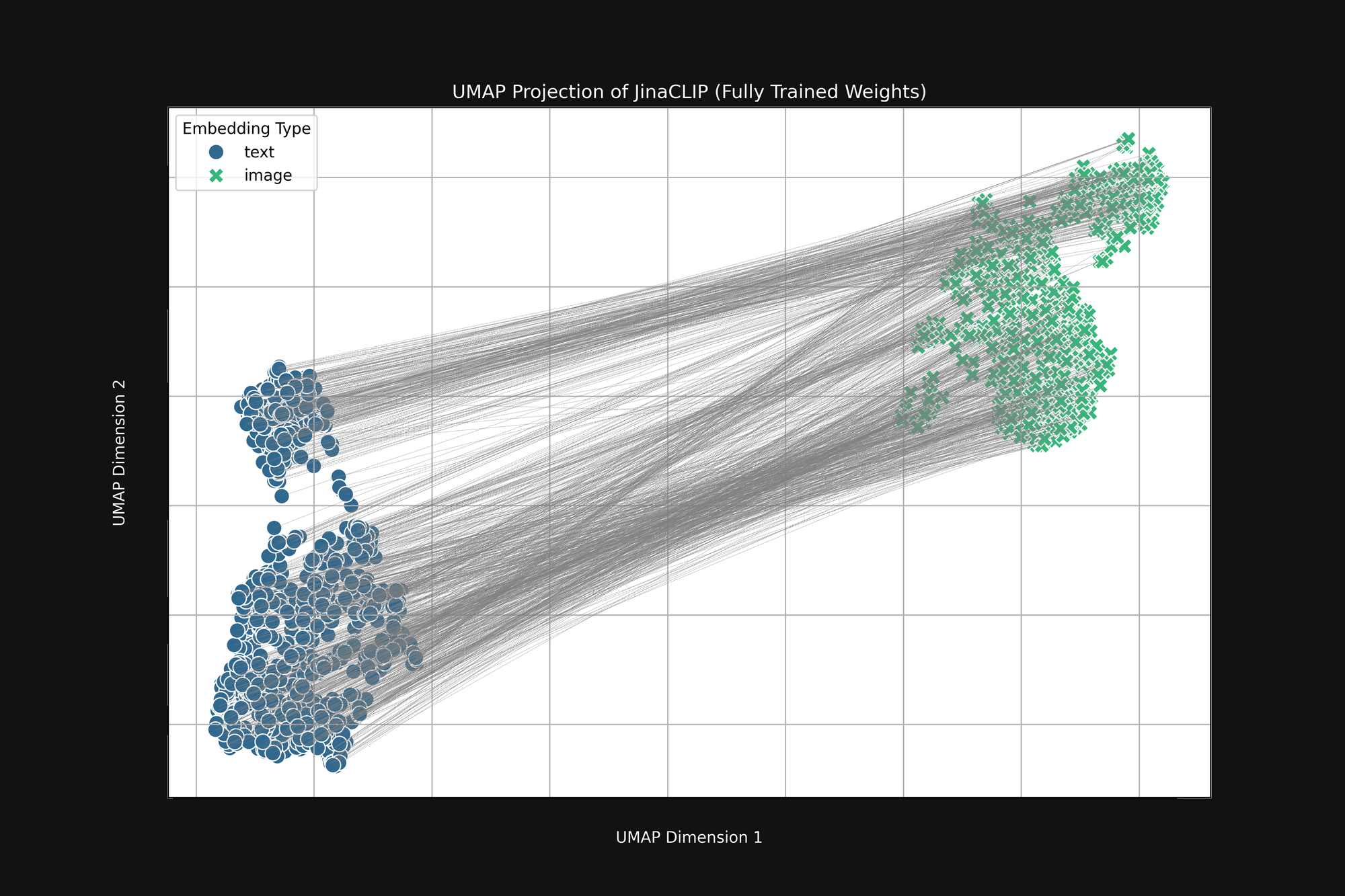

The model is prejudiced at birth and what it learns doesn’t change that. Figure 3 (below) is the same analysis of the Jina CLIP model as released, after full training using image-text pairs. If anything, the multimodal gap is even more pronounced.

Even after extensive training, Jina CLIP still encodes the medium as part of the message.

Using the more expensive OpenAI approach, with purely random initialization, does not get rid of this bias. We took the original OpenAI CLIP architecture and completely randomized all the weights, then did the same analysis as above. The result is still a truncated cone shape, as seen in Figure 4:

This bias is a structural problem, and may not have any solution. If so, we can only look for ways to correct for it or mitigate it during training.

Training Temperature

During AI model training, we typically add some randomness to the process. We calculate how much a batch of training samples should change the weights in the model, then add a small random factor to those changes before actually changing the weights. We call the amount of randomness the temperature, by analogy with the way we use randomness in thermodynamics.

High temperatures create big changes in models very fast, while low temperatures reduce the amount a model can change each time it sees some training data. The result is that with high temperatures, we can expect individual embeddings to move around a lot in the embedding space during training, and with low temperatures, they will move around much more slowly.

Best practice for training AI models is to start with a high temperature and then progressively lower it. This helps the model make big leaps in learning at the beginning when the weights are either random or far from where they need to be and then lets it learn the details more stably.

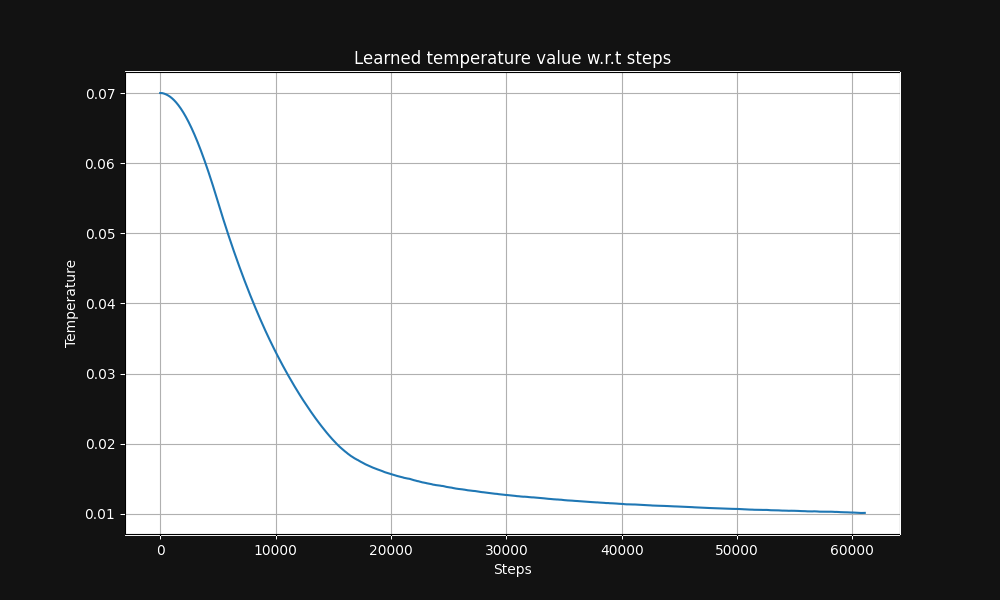

Jina CLIP image-text pair training starts with a temperature of 0.07 (this is a relatively high temperature) and lowers it exponentially over the course of training to 0.01, as shown in Figure 5 below, a graph of temperature vs. training steps:

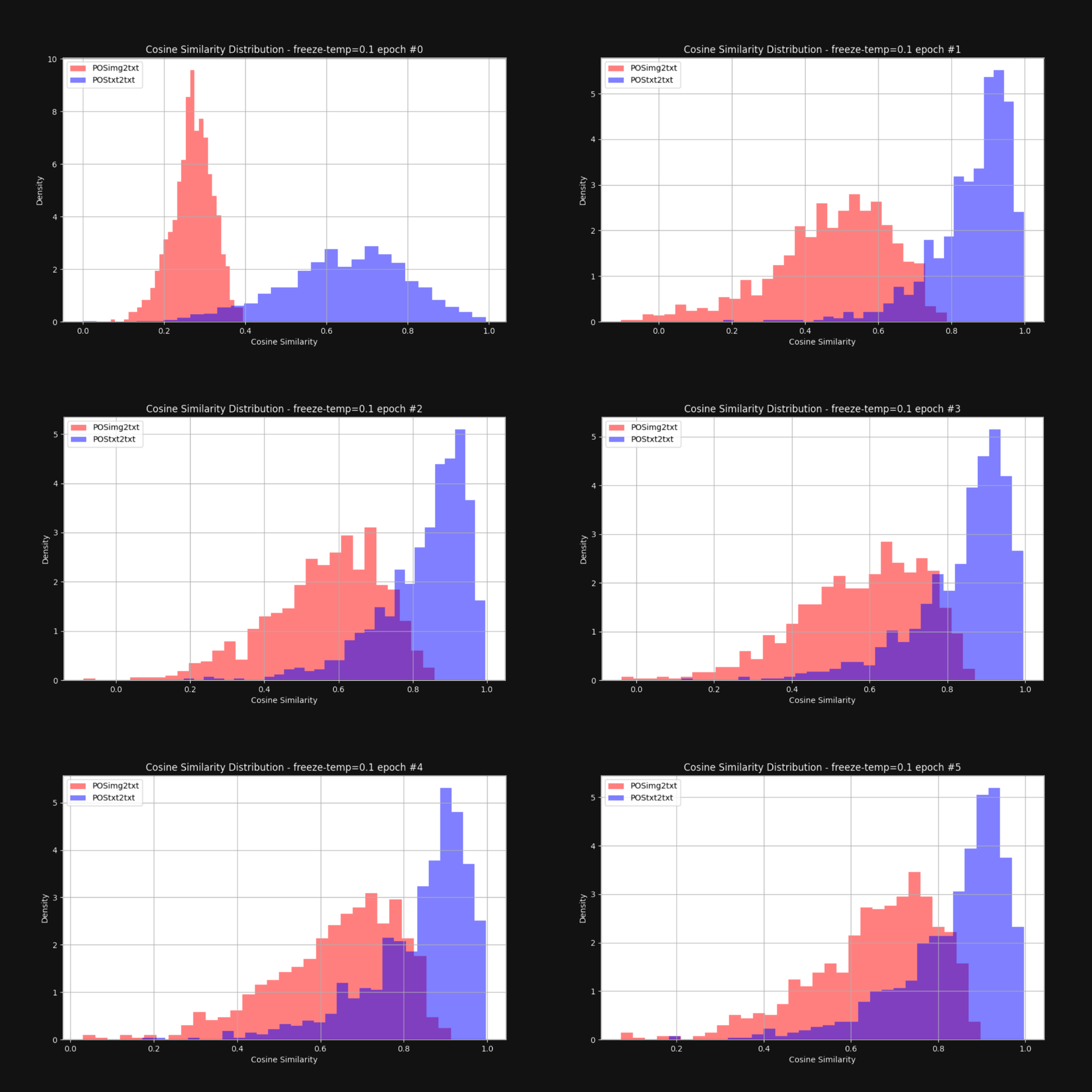

We wanted to know if raising the temperature — adding randomness — would reduce the cone effect and bring the image embeddings and text embeddings closer together overall. So we retrained Jina CLIP with a fixed temperature of 0.1 (a very high value). After each training epoch, we checked the distribution of distances between image-text pairs and text-text pairs, just like in Figure 1. The results are below in Figure 6:

As you can see, keeping a high temperature does close the multimodal gap dramatically. Allowing the embeddings to move around a lot during training goes a long way to overcoming the initial bias in embedding distribution.

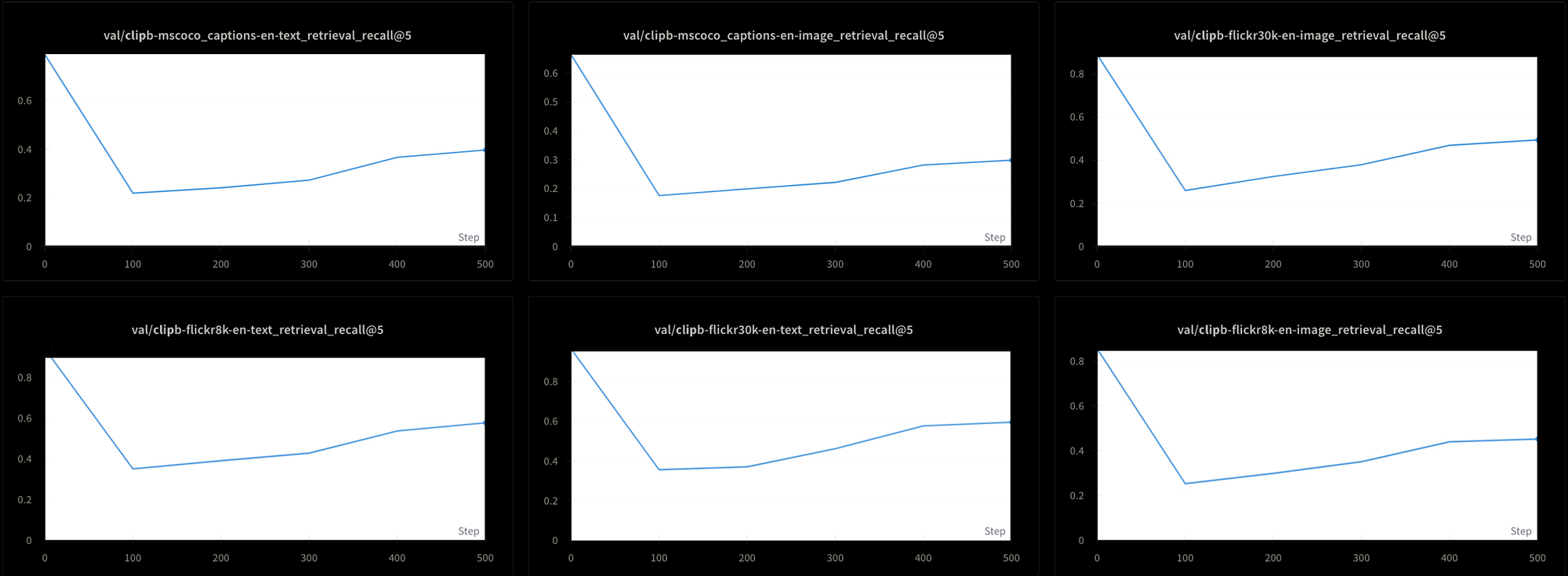

However, this comes with a cost. We also tested the model’s performance using six different retrieval tests: Three text-text retrieval tests and three text-image retrieval ones, from the MS-COCO, Flickr8k, and Flickr30k datasets. In all tests, we see performance plunge early in training and then rise very slowly, as you can see in Figure 7:

It would likely be extremely time-consuming and expensive to train a model like Jina CLIP using this constant high temperature. Although theoretically feasible, this is not a practical solution.

Contrastive Learning and the False Negative Problem

Liang et al. [2022] also discovered that standard contrastive learning practices — the mechanism we use to train CLIP-style multimodal models — tend to reinforce the multimodal gap.

Contrastive learning is fundamentally a simple concept. We have an image embedding and a text embedding and we know they should be closer together, so we adjust the weights in the model during training to do that. We go slowly, adjusting the weights by a small amount, and we adjust them in proportion to how far apart the two embeddings are: Closer together means a smaller change than farther apart.

This technique works much better if we don’t just bring embeddings closer together when they match, but also move them further apart when they don’t match. We want to have not just image-text pairs that belong together, we want pairs that we know belong apart.

This poses some problems:

- Our data sources consist entirely of matching pairs. No one would make a database of texts and images that a human has verified are unrelated, nor could you readily construct one by scraping the web or some other unsupervised or semi-supervised technique.

- Even image-text pairs that superficially seem completely disjoint aren’t necessarily so. We don’t have a theory of semantics that allows us to objectively make such negative judgments. For example, a picture of a cat lying on a porch is not a completely negative match for the text “a man sleeping on a sofa.” Both involve lying on something.

We would ideally want to train with image-text pairs that we knew with certainty were related and unrelated, but there is no obvious way to get known unrelated pairs. It’s possible to ask people “Does this sentence describe this picture?” and expect consistent answers. It’s much harder to get consistent answers from asking “Does this sentence have nothing to do with this picture?”

Instead, we get unrelated image-text pairs by randomly selecting pictures and texts from our training data, expecting they will practically always be bad matches. How this works in practice is that we divide our training data into batches. To train Jina CLIP, we used batches containing 32,000 matching image-text pairs, but for this experiment, batch sizes were only 16.

The table below is 16 randomly sampled image-text pairs from Flickr8k:

To get non-matching pairs, we combine every picture in the batch with every text other than the one it matches. For example, the following pair is a non-matching image and text:

Caption: A girl in pink picks flowers.

But this procedure assumes that all texts matching other images are equally bad matches. This isn’t always true. For example:

Caption: The dog sits by a snowdrift.

Although the text doesn’t describe this image, they do have a dog in common. Treating this pair as non-matching will tend to push the word “dog” away from any image of a dog.

Liang et al. [2022] show that these imperfect non-matching pairs push all images and texts away from each other.

We set out to verify their claim with a fully randomly initialized vit-b-32 image model and a similarly randomized JinaBERT v2 text model, with the training temperature set to a constant of 0.02 (a moderately low temperature). We constructed two sets of training data:

- One with random batches drawn from Flickr8k, with non-matching pairs constructed as described above.

- One where the batches are intentionally constructed with multiple copies of the same image with different texts in each batch. This guarantees that a significant number of “non-matching” pairs are actually correct matches for each other.

We then trained two models for one epoch, one with each training dataset, and measured the average cosine distance between 1,000 text-image pairs in the Flickr8k dataset for each model. The model trained with random batches had an average cosine distance of 0.7521, while the one trained with lots of intentionally matching “non-matching” pairs had an average cosine distance of 0.7840. The effect of the incorrect “non-matching” pairs is quite significant. Given that real model training is far longer and uses far more data, we can see how this effect would grow and heighten the gap between images and texts as a whole.

The Medium is the Message

Canadian communications theorist Marshall McLuhan coined the phrase “The medium is the message” in his 1964 book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man to emphasize that messages are not autonomous. They come to us in a context that strongly affects their meaning, and he famously claimed that one of the most important parts of that context is the nature of the medium of communication.

The multimodality gap offers us a unique opportunity to study a class of emergent semantic phenomena in AI models. No one told Jina CLIP to encode the medium of the data it was trained on — it just did anyway. Even if we haven't solved the problem for multimodal models, we at least have a good theoretical understanding of where the problem comes from.

We should assume that our models are encoding other things we haven’t looked for yet due to the same kind of bias. For example, we likely have the same problem in multilingual embedding models. Co-training on two or more languages probably leads to the same gap between languages, especially since similar training methods are widely used. Solutions to the gap problem may have very broad implications.

An investigation into initialization bias in a broader array of models will likely lead to new insights as well. If the medium is the message to an embedding model, who knows what else is being encoded into our models without our awareness?